How dare we call them “dummies”! They are actually a family of intelligent specialists who make an enormous contribution to occupant safety. It’s time to get to know them better.

Every day they are restrained by seat belts at high speed, slammed into airbags, objects or fellow passenger dummies, and made to suffer strain and injury. They are designed to endure serious car accidents and put their “lives” on the line over and over for our safety. But why and how exactly do they do this?

Extremely sensitive

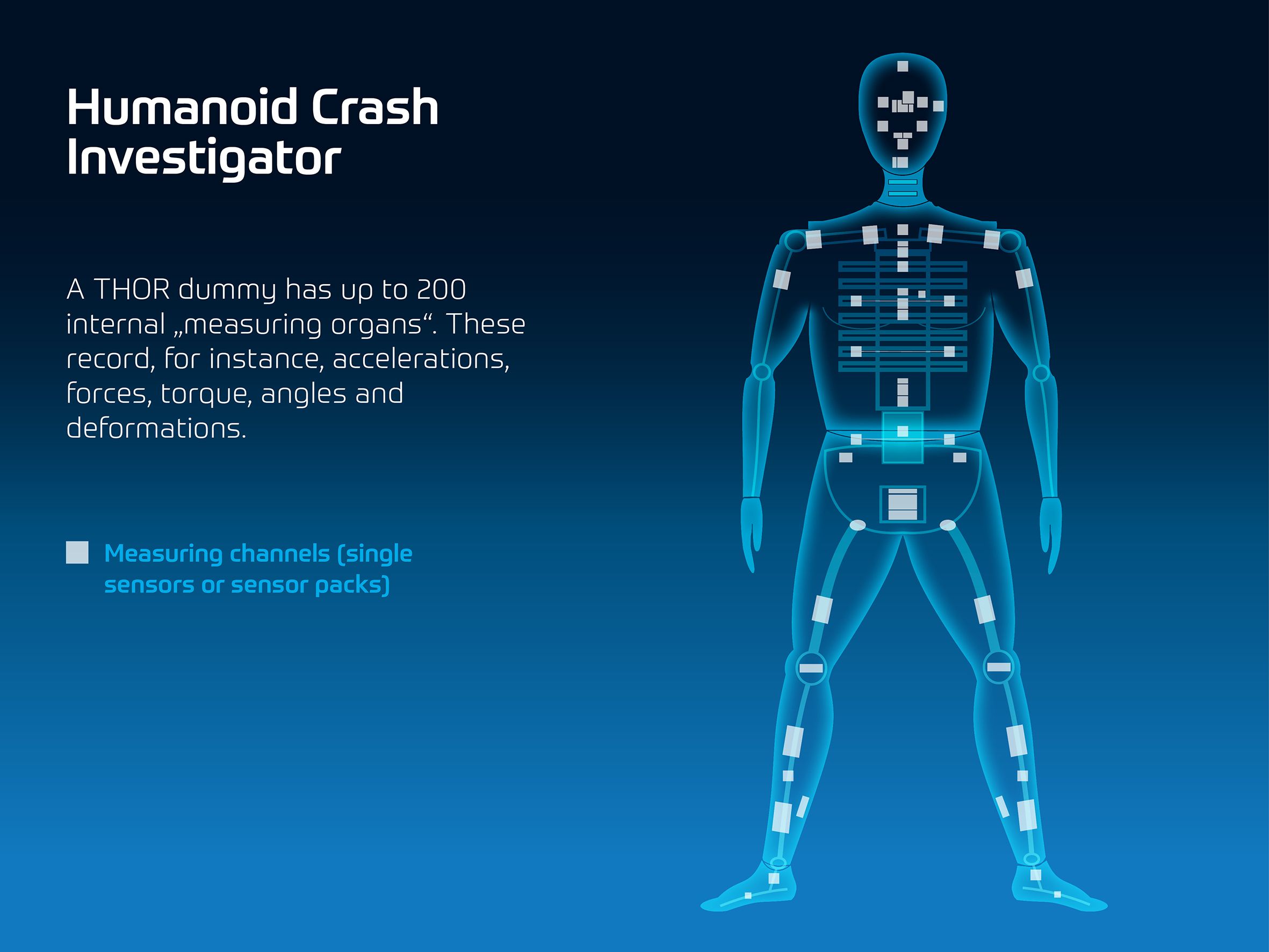

A modern crash test dummy is a powerful measurement-taking instrument modeled on the human body with a huge capacity for detecting what it is experiencing: With up to 200 sensors, it electronically senses and communicates what it experiences in a crash. These measuring points are distributed over the entire body. There can even be a so-called “sensor six-pack” in the dummy’s head.

A common origin

Three-quarters of today’s crash test dummies have common family roots in the USA and are manufactured by the world market leader in this area, Humanetics, which is headquartered in Farmington Hills, Michigan. Crash test dummies are officially referred to as anthropomorphic test devices (ATDs).

Humanetics’ customers are virtually all automotive manufacturers and major suppliers (tier 1). Most of the ATDs used by ZF come from this company or its predecessor company. However, the very first dummy was not intended for use in cars. It was called Sierra Sam and used to test aircraft ejection seats, harness systems, and life jackets for the US military.

Frequently discussed in terms of ethics

Before the first ATDs were created, human corpses and animal cadavers – especially monkeys and pigs – were often subjected to crash tests. The engineers thus had at hand the biomechanical limit values needed for the most humanoid dummy designs possible.

Ultimate assurance from self-experimentation

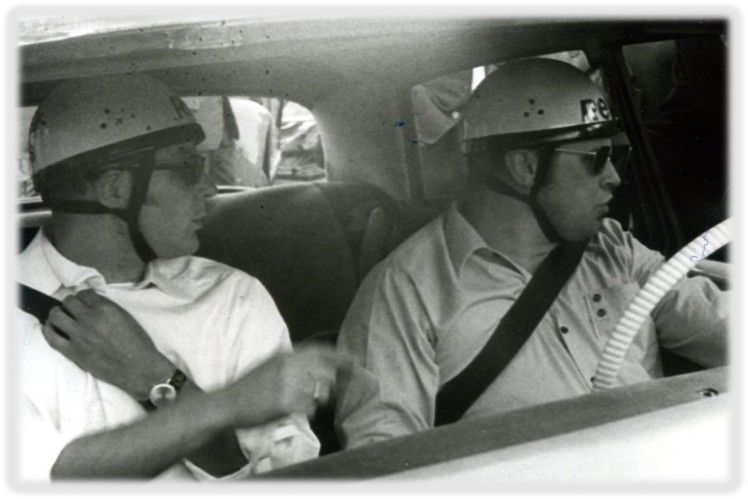

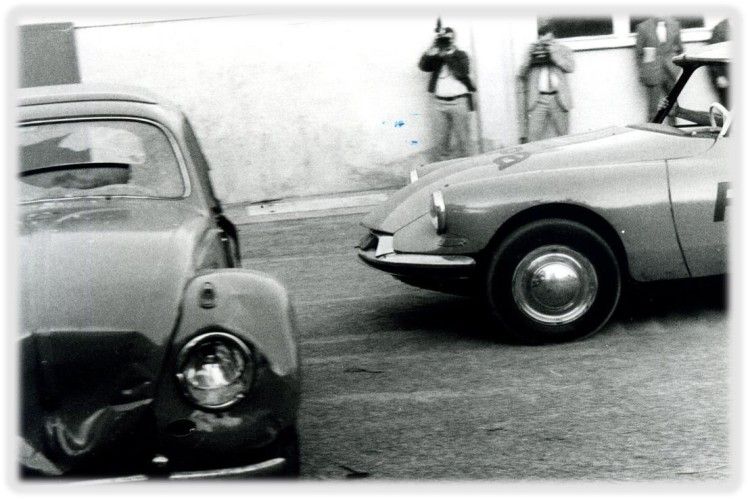

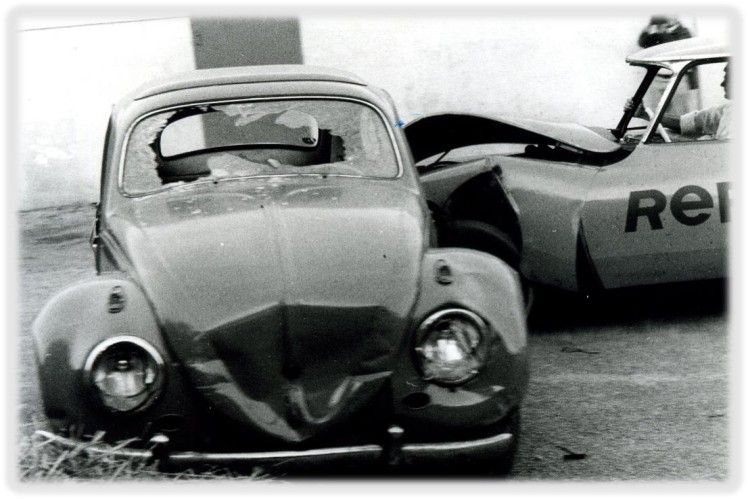

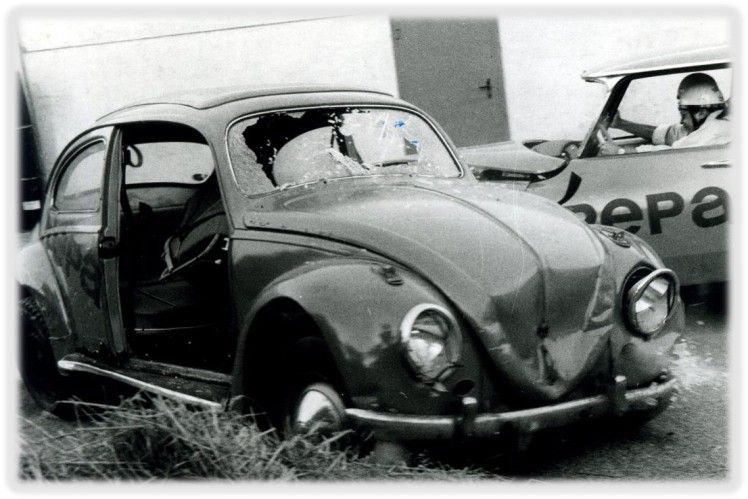

In the 1970s, managers themselves sat down in the vehicles. However, their mission was not to serve as human guinea pigs. At customer presentations, they wanted to prove (in non-dangerous crashes) how convinced they were of their own occupant safety systems (see image gallery).

A global extended family

High life expectancy

Like real people

The basic skeleton of a dummy is of steel and aluminum, and the skull is made of cast aluminum. Rubber disks between the bone elements make the spine flexible. Ribs made of steel and polymer materials form the chest. Elastic vinyl skin covers the entire body, and the tissue underneath is made of foam. Screws hold the joints together. Dummies are thus built to closely mimic real people but with completely different materials. Nevertheless, they are anatomically very similar to a human body.

THOR, the best dummy in the world

Since 1976, the Hybrid III 50th Percentile Male (HIII-50M) has been the benchmark for dummies: originally 1.75 meters tall and weighing 78.2 kilograms, it corresponded to the average (male) person at the time. However, the latter grew in size over the decades, becoming heavier and older. At the same time, the test requirements were made more stringent. This has led to more and newer versions of the Hybrid III, which holds the record for number of participations in car crash tests. In the meantime, only the very oldest ones have been retired, with one of them immediately finding a new home in the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

Now THOR wants to take over the position previously occupied by Hybrid III; and there are already three of them in use at ZF. This dummy resembles humans even more, has more authentic movements, and outputs even more precise measurement values. It also provides 3-D information for every crash, which is exactly what is needed for running simulations with virtual dummies.

So the next time you buckle up for a drive, take a moment to appreciate that your vehicle was helped to made safer than ever before because of the “crash clan”!

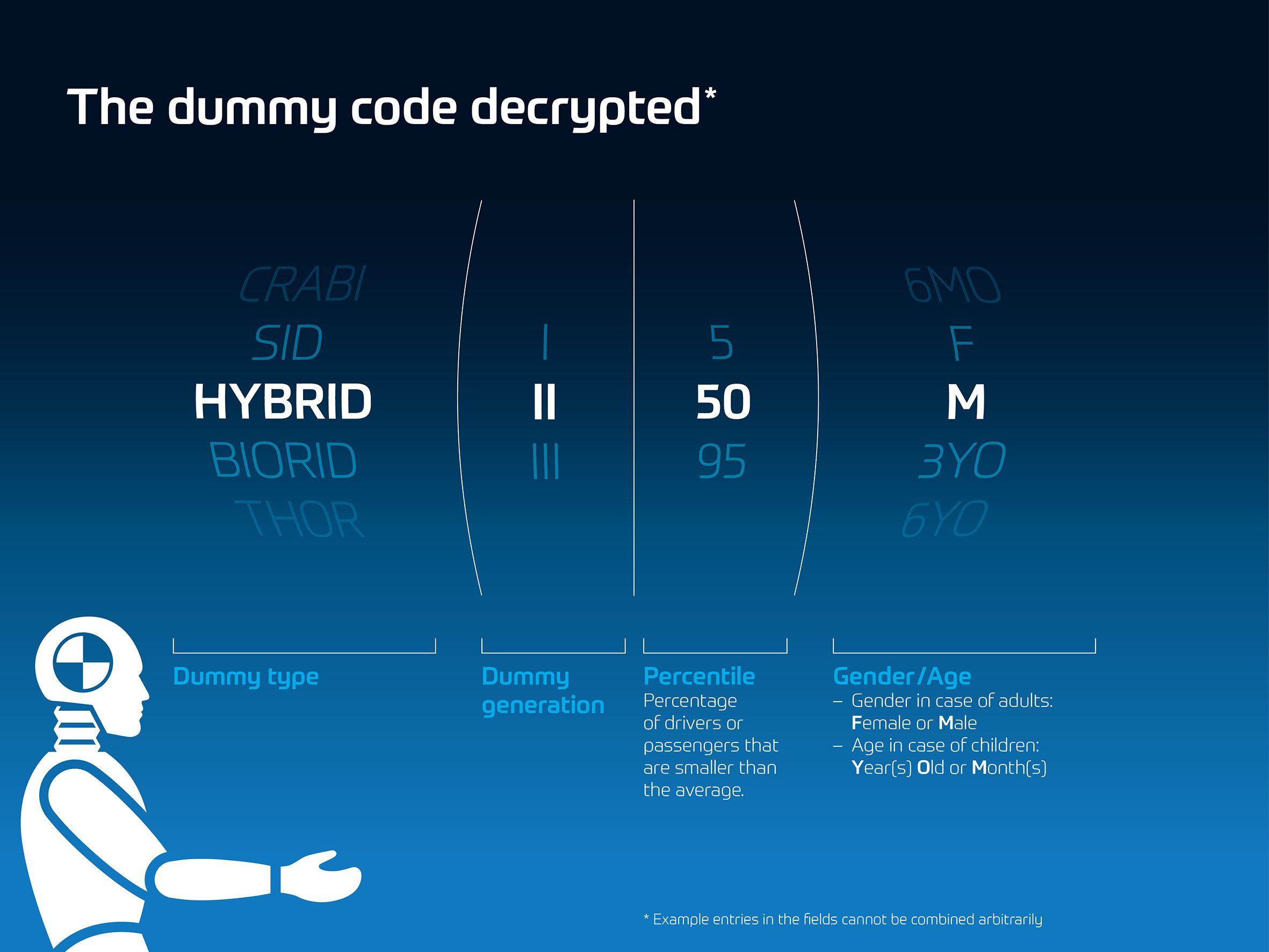

The ATD types

A single dummy that precisely imitates the locomotor system of adult humans in every direction does not (yet) exist. However, there are specialists for every possible case.

Hybrid: The name has its origins in the late 1960s. Using the two available dummy types (VIP-50 and Sierra Sam), General Motors developed a new dummy that could meet the company’s proprietary needs. Hybrid dummies are primarily designed for frontal impact.

SID: The abbreviation stands for Side Impact Dummy, which also describes its preferred field of application. With its mechanical structure, it imitates human movements in lateral collisions (load cases) and is designed to do so as accurately as possible. Developed around 1980, this dummy’s missing forearms make it unmistakable.

BioRID: The so-called Biofidelic Rear Impact Dummy was created in the 1990s. It is based on research conducted by the Swedish Chalmers University together with car manufacturers Saab and Volvo. In crashes, it behaves in a more human-like manner than the Hybrid III, that is, it exhibits more biological fidelity. This is primarily due to the new spine, which is more flexible and authentic. BioRID is still recommended today, especially for rear impact tests.

CRABI: The name is derived from Child Restraint/Air Bag Interaction. It describes a group of three toddler dummies. These dummies imitate children at the ages of 6, 12, and 18 months in terms of size, weight (50th percentile in each case) and flexibility. It is used to test child restraint systems in all impact directions as well as with and without airbag deployment.

THOR: The Test Device for Human Occupant Restraint is the latest, most human-like dummy. It is the successor to the Hybrid III 50th Percentile Male. It greatly surpasses the previous model in terms of spinal and pelvic kinematics and facial sensors. The measuring equipment is not only more extensive, but also records much more precisely. In the Euro NCAP, THOR will be used from 2020 for a new frontal crash test, the MPDB (Mobile Progressive Deformable Barrier) test: this test also evaluates how occupants interact with fellow passengers involved in an accident.

Achim Neuwirth has been writing for ZF since 2011. He has specialized in writing texts about all kinds of car-related topics: from vehicles to the technology behind them, to driving and traffic.

Next Stories

Meeting the Challenge of Knee Airbags

One of the most exciting parts of the automotive industry is the idea that there is always a way to make something lighter, smaller, safer.

An Airbag that is Quick to Offer Protection

Head-on collisions can be dangerous. This even holds true for collisions on the opposite side to the occupant, as the impact can throw the occupant’s body toward the middle of the vehicle.